Lana Vegman, PharmD, Envision Pharma Group

Strictly defined, a poster is a paper print designed for display on a wall or vertical surface.1,2 Posters can include visual images, text, or both. The printed poster dates back to the 1840s, following the advent of color lithography, which the printing industry refined and ultimately automated to make mass production possible.2

Over time, the media for these creative visual pieces has evolved from paper, cardboard, photographs, laminated paper, and cloth, to electronic posters (e-Posters), all in an effort to increase reach and bring attention to the information being conveyed. A successful poster captures the viewer’s attention, and communicates the key points clearly and succinctly.

Medical conferences generally include sessions for scientists to display the results of their research in a poster format. These research posters are a good way of presenting information to reach a large audience, particularly when they are made available in an electronic format after the meeting to individuals who did not attend the congress.

At a congress, poster presentations are less coveted than oral presentations by researchers because posters are less prestigious and generally have more limited impact and reach.3 However, posters play a critical role in medical conferences because they are more numerous than oral presentations, and they provide an opportunity to display not only completed research and novel data that might impact clinical decision-making, but also preliminary findings and ongoing research that provides the larger scientific community with the latest developments in their field.

While posters at congresses certainly provide value, there are areas that can be, and are being, improved upon. A study published in 2009 demonstrated that among 142 posters reviewed at a national meeting, 33% were cluttered or sloppy, 22% had fonts that were too small to be easily read, and 38% had research objectives that could not be located in a one-minute review.4

Recent Trends

Recent trends have shown a shift away from traditional paper-based posters to e-Posters, which were introduced and have grown in popularity in the past five years at medical congresses. An e-Poster utilizes a large monitor and computer to display the poster, and may allow for some multimedia content. While it provides an opportunity to more effectively convey the information and enhance visualization and appeal, it also requires both computer-savvy presenters and viewers to be able to make the most of the content. Additionally, the graphics in an e-Poster become more critical components of the presentation, and these must be appropriately designed to ensure maximal functionality and ease of use; issues with these elements may deter viewers from being able to review the entire e-Poster content, thus missing critical information.

Around the early 2010s, quick response (QR) codes were introduced as a novel way to extend the reach of printed poster presentations beyond the congress. Anyone who has walked through a crowded congress hall full of posters, but with limited time, immediately recognized the impact of quickly scanning QR codes to capture electronic versions of the posters for reading in detail later, and spending more time interacting with presenters. An added advantage of QR codes is that they eliminate the need for printed handouts, which can be burdensome to organize and store, or all too quickly become trash.

Augmented Reality

As the poster has evolved, one unresolved question remains at the forefront – how does one combine engaging graphical elements with explanatory text, while still providing the necessary details without any clutter? One solution may be Augmented Reality. While this concept has been used in cinema for some time, augmented reality more recently has extended its reach to scientific conferences.

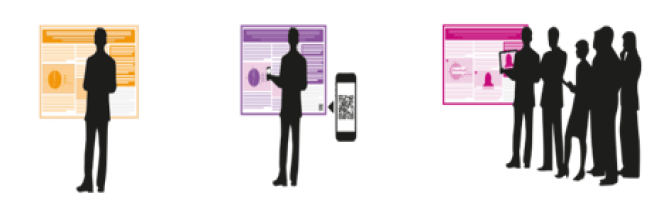

Augmented reality is a way to add digital content, such as videos, additional graphics, text, tables, figures, and other 3D experience to the traditional paper poster (Figure 1). This is done through use of various apps that are launched using a particular launch point on the poster through a smart device (eg, phone, iPAD). The launch point is treated as a “hot spot” that transforms sections of the poster from its static form to provide user access to information beyond what is visible on the printed poster itself. Augmented reality provides an opportunity to add more depth to and interaction with a poster, without disrupting conveyance of the main points.

Figure 1: Evolution of a poster – use of Augmented Reality 5

Presenting authors are generally required to stand by their poster for one to two hours, sometimes longer, to provide an overview of the findings and address questions. Often, they are asked the same question repeatedly by different viewers because space limitations on the printed poster did not allow inclusion of enough detail. Adding an icon to a critical figure, table, or piece of text can give the author the ability to provide information that is not physically printed on a poster that will enhance understanding of the content, stimulate discussions, and preempt questions.

Augmented reality also allows the attendee to interact with the poster, even when the presenting author is not available. And, if the printed poster also includes QR codes, attendees can capture electronic versions of the poster, along with the additional augmented reality content, as a take away.

While there are several benefits to exploring this new technology, when considering augmented reality, additional timing and cost for development of the interactive components and graphical elements need to be carefully weighed. Depending on the level and complexity of the animation and graphics, an additional 2-3 weeks should be planned to allow sufficient time for development and quality check of the added components and final poster. While the costs for development vary, an assessment of the complexity and number of augmented reality “hot spots” desired in a given poster can help guide the additional cost required.

Although platform presentations are widely considered more prestigious, poster presentations can offer a better opportunity for attendees to engage with their colleagues to more fully assimilate the newest advancements in their area. From its start in the 1840s as a simple paper image to the present, where use of technology makes it possible to create additional interest and provide more depth and dimension, the scientific poster has had the same goals of conveying the latest research findings, stimulating further research, and for key findings, impacting clinical decision-making. The only difference being in how the information is served up and taken away.

All this makes you wonder, what will tomorrow bring?

Disclosure: Editorial support for this article was provided by Alison Gagnon, PhD, of Envision Pharma Group

References

- Gosling, Peter. (1999). Scientist’s Guide to Poster Presentations. New York: Kluwer.

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poster. Accessed on January 8, 2016.

- Hess GR, Tosney KW, Liegel LH. Creating effective poster presentations: AMEE guide no. 40. Med Teach 2009;31:319-21

- Swales, J.M., & Feak, C. (2000). English in Today’s Research World: A Writer’s Guide. Michigan: Michigan University Press.

- Figure courtesy of Envision Pharma Group. All rights reserved